The backstory behind my TED talk.

and the tragic difference of knowing, but not believing what you know.

WRITING THIS TALK was easy because it was just observation of the obvious. I, like many of you I imagine, have the disease of people-pleasing. I learned it as a kid. The routine is simple: You’re crying, your parents give you the ultimatum to stop crying or else they won’t be pleased, and if the ones you rely on to survive aren’t pleased they might not take care of you, and if they don’t take care of you, you might die. So, you choose to please them, to stop crying, so that you might live.

I’m all grown up now and I’m well aware that I will be fine if I don’t please anyone. Under ideal circumstances, I would convince myself that I will be okay, even if people don’t like me. But that formula of Disappointment = Death, never got removed from my factory settings. So therefore, please everyone, says my self. Adjust until they like me—agree until they like me. Once they like me, I’ll be safe. This is the tragic difference. I know I will safe if I disappoint people, but I don’t believe it. I know what I need to do with my life, but I can’t change it. I can’t change it because I want to live, and there is something suicidal about rebirth. It’s not just about shedding the old ways, but about letting that old self die, about slightly letting go of wanting to survive so bad. This is why no matter how many phases of morning routines, cold baths and affirmations and self-help books, we tend to drift back to default factory settings. The factory reset requires a little bit of death. To loosen the grip on survival so that we might live a little. Maybe this is all a little cliche, but maybe this cliche exists for a reason.

THE TEAM AT TED was not thrilled with the concept of my one-man play where I murder a version of myself onstage. Understandable. So instead, I broke up with myself onstage. Never mind how I got the TED gig. An email came through out of nowhere asking if I’d be interested in doing a quick, 6-minute talk about “something interesting.” That’s it. “Interesting? Interesting how?” Oh you know, just interesting in a good kind of way, interesting. How they found me, why they wanted me, what they thought I, a lowly Internet personality, had to say to an educated crowd with actual jobs, the answer is blowin’ in the wind. I am an expert in nothing. I have absolutely nothing to add to the millions of recycled wisdom and jokes. My home is fiction. So, I told TED I wanted to do a one-man play type of thing, and they said, “fine.” A few months later I performed my act for the TED curation board and it was almost 9 minutes (way over my allowed 6 minutes). I said I would cut it down, but they actually liked it enough to give me the whole 9 minutes. “Don’t edit a thing.” I slept so badly that night knowing as a writer, I will never receive that feedback again and that everything after this will savor anticlimax.

They treat you like a celebrity. You get flown out business class, they put you up in a swanky hotel, and give you free beef jerky. I wasn’t nervous because I thought this was going to be a TEDx event or something. When I arrived for rehearsals the day before the event, I saw the nearly one-hundred-person crew all dressed in black, backstage equipped with military-grade sound gear, computers and walkie-talkies going off, and cranes setting up the stage. I realized it was the real thing. This is an actual TED talk. Daunting, yes. Nervous? Not really. I knew the material and I knew it was good—because it was real, and you don’t have to work as hard when you’re telling the truth.

My monologue involves me wearing a bathrobe onstage (to imply I’ve just gotten out bed). On the day of, I lost the bathrobe while I was at breakfast. The hotel thought it was laundry. I spoke with the manager but unfortunately there was “simply nothing they could do about it,” but rest assured, they were trying their best, so thank God for that, because I was worried they were half-assing it. Did they have a robe they could lend me? Yes, but it was the wrong kind—it cut off above my knees so I was more like a skirt. So, with three hours before I’m supposed to go up on stage, I turn to crime. I take the elevator down to the hotel spa and salon. The receptionist was on the phone in the back office. She gave me a “one moment” sign with her finger. I smiled, waved, and stole a robe.

I Uber over to the venue. I arrive in the green room backstage in my robe and slippers and I eat beef jerky. There is a live feed in there about two seconds behind what is being said on stage. Malcolm Gladwell goes up and talks about something I don’t really catch because I’m going over my own script. By the time he was done and I sit down, all I hear him say is, “I’m sorry.” And applause. I don’t know what that was all about, but I guess he was sorry and the audience was happy about that. Then, what else can I say? I went out there, did the act, and then it was done. It was almost anticlimactic because I’d been rehearsing it for so long only to be over instantly. There were a few TED crew members from the UK. They were particularly moved by my act, even at rehearsals. When I stepped off stage, one of them cried and said, “thank you for that” as I walked by. Later, one of them came up to me and I asked her why it strikes a chord with the English, and she said, “There is something inherently British about knowing how to save yourself, and being unknowingly unable to.”

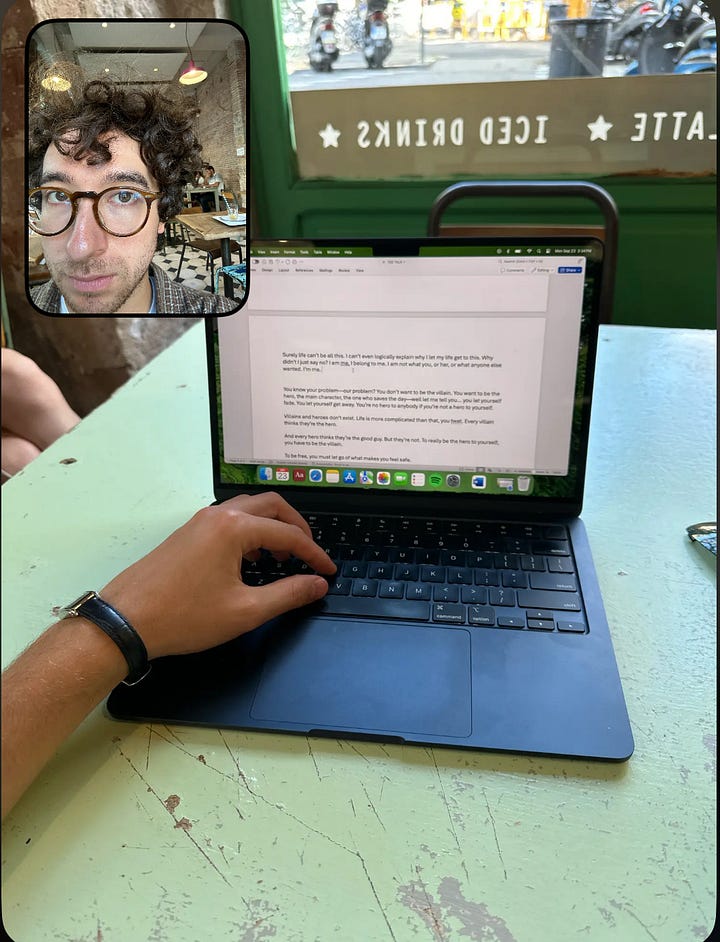

SO THAT’S HOW the TED talk went. It was of course, a terrific honor to be a part of something like that. My original title was just, “Confessions of a People Pleaser”—the “recovering” bit was added by the folks at TED. It was nice of them to assume that. I am here, wearing that same stolen robe, writing about people-pleasing now, having written a monologue about people-pleasing and performing that monologue onstage, and yet I am still what I seemingly recovered from. I will still agree with you that a movie was great when I thought it sucked. And the irony is that the only time I ever feel free from my people-pleasing ways is when I write and make things and thousands of people see it. For some reason, I can do that and ignore the validation. Making stuff up is my one way to actually be honest, and maybe that is why it’s write or die for me, because it is the only way I can be found. I still crave people’s affection and approval in real life because I am not ready for the ego to die a little. I’m right at the edge and I can’t jump. All the motivational books and affirmations in the world can’t make you do it. They can take you right up to the edge but the rest is up to you. I’m sure I will find a way out, just like I found a way to tell the truth, but I certainly haven’t done so yet. For now, I keep nodding even when I don’t want to. For now, I keep writing, and writing, and writing. Maybe at very least, if I try to tell the truth, I’ll start to believe what I already know.

This substack is the reason I have my own now. Even when I'm in a reading rut your writing is immune to the illness. Thank you for being the push I needed to start writing. Thank you for writing. Your work matters.

The world works in mysterious ways...

I met you the day before this TedX randomly. I was walking down the street in Midtown Atlanta singing a silly jingle to my friend about how I wanted a brownstone, imagining doing dishes with a Noah Baumbach type. A few minutes later we head into Publix to grab some movie treats, ice cream was our choice, and I glance over and see you in the checkout line and say to my friend, "Hey, look, isn't that American Baron?" And he agrees and convinces me it's okay that we walk up to you. I think to myself that you seem to be mourning something, a relationship maybe. Maybe just the Orville Reddenbacker (or was it Act II, idk) / a plethora of snacks that cued me in. I have no clue. The last thing you wanted to do is talk to strangers probably, thanks for giving us a minute of your time anyway though.

Then today, whilst lost in conversation with myself, the image hits me. It's the abstract drawing my 72 year old caricature of a therapist keeps coming back to (the one I keep staring blankly at, the truth of it not sinking in.) It's a blob of violet which is my true self, covered up by a bigger blob of black which is my false self, the one he says I've confused myself for. And he's right. My whole life has been a lie. I haven't done a damn thing because I wanted to. It was her who wanted these things: that degree, those friends, that portrayal, that shame. And I hated it. I realized, much like you did, that I haven't even lived my own life.

... Now I have to figure out how to unpiece that entangled being, day by day, but at least right now (who knows if I do tomorrow) I feel a change internally.

And then, there you were, in my email inbox sharing a similar story at such a peculiar timing. Just felt like I should share. Weird world we live in.

As always, thank you for your art, Baron.